Literature Review

Since the introduction of the 1984 Canada Health Act, Canadians have enjoyed the benefits of universal medicade; however, the same cannot be said for its prison population [1]. Although there is disagreement about how those who break the rules should be punished, there is little discourse on the basic human rights of individuals who are incarcerated [1,2]. Simply put, the most vocal voices that argue for more intense criminal punishments often have little or no first-hand account of the day-to-day experiences of those serving time [1]. Although landmark legislation of the Canada Health Act transitioned Canada into a new healthcare era, Canada’s incarcerated population purposely1 left out of its benefits [1,3]. Whether for political or punishment reasons, it does not matter; no system can exist that does not meet the basic human rights of the individual, incarcerated or not [1,4–6].

Today, Canada’s federally incarcerated population, or those who face sentences greater than two years, falls under the mandate of the Corrections and Conditional Release Act (CCRA) of 1992 [1]. Under such measures, healthcare is financed and administered by the Correctional Service of Canada (CSC), under the authority of the federal ministry of public safety. Although such arrangements have been subject to decades of debate, their outcomes are clear, as Canadians incarcerated have higher rates of mortality and morbidity than those within the free community [1,6–8]. For the purposes of this paper, such figures will not be a considerable topic of discussion due to the lack of currently available evidence and clear disparities in health and outcomes.

In the 26 years since the establishment of the CCRA, limited progress has been made in addressing health inequalities within Canada’s federal carceral system [1]. As the scholarly literature continues to accelerate understandings of the intersections of Canada’s criminal-legal system, or rather “non-system” as coined by some, the day-to-day functions of CSC’s penitentiaries remain stagnant [1,6]. Although discourse and debate about degree and causation dominate both scholarly and contemporary communications, the original dialogue that sparked such matters becomes seemingly trivialised to the larger picture [9–11]. In other words, the focus shifts away from the individuals struggling to survive the dysfunctions; everyday left of their sentence, surrounded by barriers purposefully erected to restrict their freedoms, governed by legislation as minuscule as society cares for them [9–11]. While radical change will undoubtedly be part efforts of a future system that upholds justice and human dignity, we cannot neglect the individuals who live within the walls of today’s dysfunctions. Critically, it is this resilience that continues to drive progressive change and the consensus on how society should approach crime, punishment, and rehabilitation [6,12,13]. While it is easy to label the dysfunctions of the CSC, and their administration and provision of healthcare services, its effects will simply add decades of inaction since the CCRA’s inception. Hence, this paper uses an individual-based approach to target the cyclic health inequalities generated from the dysfunctions of the CSC’s healthcare systems. Given the uncertainties and complexities of the release and transfer of an individual between healthcare authorities, this paper seeks to introduce an intervention framework that fits the current logistic timeline, so that consensus can be reached for the promotion of health within the legal, financial, and political bureaucratic constraints.

Commentary

Solving any systematic problem, let alone all of them together, is as complex a challenge as even selecting a place to approach it. Moreover, reintroducing new frameworks to intervene in any challenge is not without complication, as new problems could arise or efforts could go without any benefit. Although a complex web of flawed moving parts exists, such an intervention should not ignore its existence. Therefore, the purpose of this intervention is to use the systems already present to build on the already known strengths and develop a meaningful short-term impact on a current and pressing challenge.

Healthcare Liaison Officer

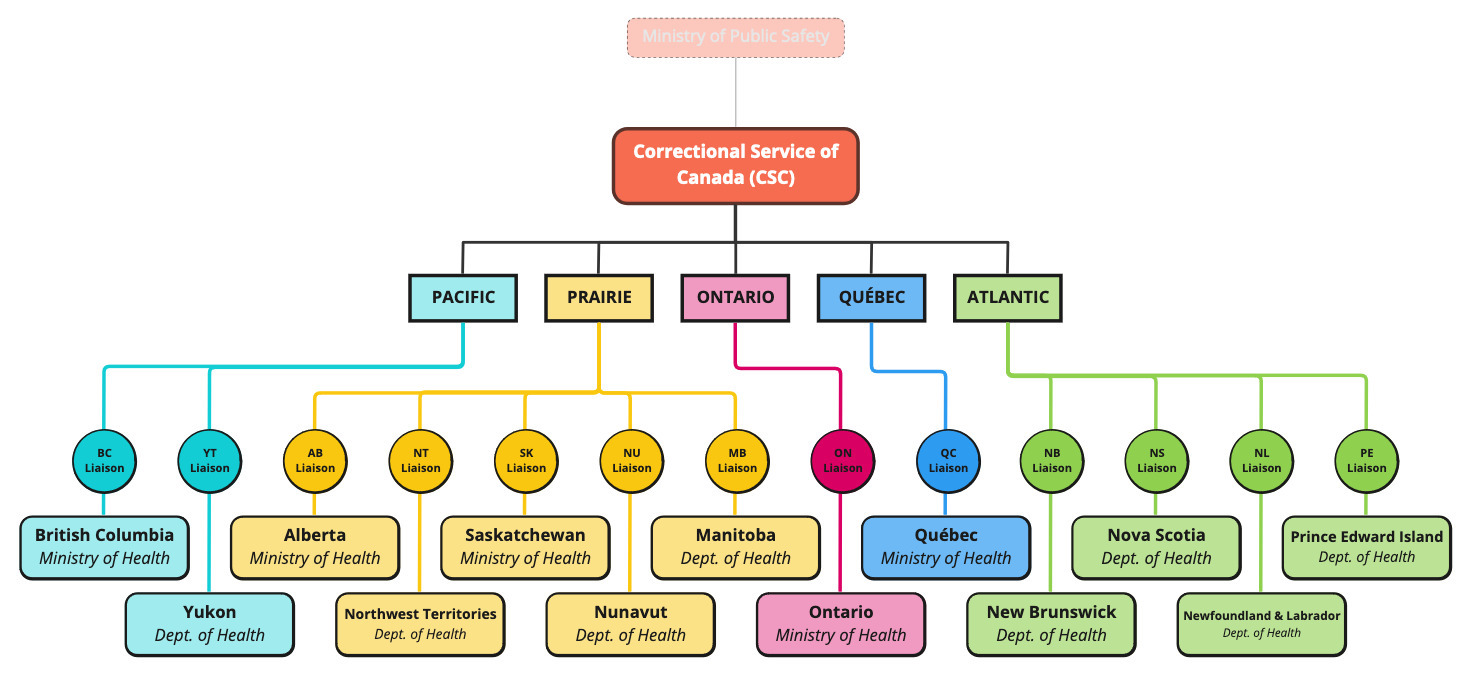

Given the humanistic approach of this paper, individuals working within the Healthcare Liaison Officers’ (HLO) authority set out their mandate. Along the already established logistic and managerial chain of command, the HLO would be a front-line staff member responsible for bridging the divide between the CSC and provincial and territorial health authorities. Although all provinces and territories must provide universal medicare under the provisions of the Canada Health Act (1984), vast provisional, administrative, and logistical differences bring rationalised complexities and quirks [1]. While significant financial burdens would exist, we argue that thirteen HLO’s should exist, such that they can provide accurate and knowledgeable insight in navigating their respective system. Figure 1 provides a visualisation of the location HLO’s have on the managerial chain within the CSC and Ministry of Public Safety.

HLO’s will work one-on-one with individuals prior, during, and after their release, ideally to the maximum caseloads permit. Working alongside parole officers, family and friends, and other stakeholders individually involved will provide education of available services and act as a middleman in transferring one’s healthcare file. With the location under the CSC’s commissioner, this intervention takes advantage of the strengths of the current system to decrease managerial expenses and bureaucracy2 While the HLO’s are core to this intervention, the outcomes remain in control of those at the forefront of the carceral system. Critically, this is not to say that these individuals have total control over the fate of their actions. The choice to remain engaged with the healthcare system is deeply ingrained in their intersectionalities and beliefs about its effectiveness for their own life [7,14]. Although the health and wellness of individuals ultimately come to their own willingness to access and engage in services, it is the responsibility of the system to provide ease in accessing realistic care. With consideration of the “duopoly of responsibility”, the following sections of this paper will discuss the two core mandates of this framework: education and continuity of care.

Healthcare Education

The ladder of this statement is critical to focus on, as people facing incarceration are less likely to engage in the healthcare system. When within the carceral setting, much of the healthcare received was often outside the individuals’ control or with heavy strings attached, such as being required to be directly witnessed by correctional staff without objection.

For any Canadian, let alone individuals incarcerated, the health systems of Canada are complex, often changing, and vague [1]. For individuals who transfer from the CSC authority, such issues are magnified from years of solitude, before even considering the demographical position in which the prison population of Canada is based [1]. Although information is critical to maintaining health, the ability to speak and interact with another person who understands one’s position is transformative [15]. Understanding the hesitations people face when simply speaking with a healthcare professional after years of distrust and trauma from authoritative figures is the principle of this mandate [14,15]. Furthermore, the ability to form such interpersonal relationships after release is reflected in lower mortality and morbidity rates [2,9,10,15]. Although its effects have been limited to those with quality relationships before and during their sentence, the presented intervention presents an opportunity to extrapolate such effects. Furthermore, while providing education and guidance to the available services that meet the needs of an individual is progressive alone, creating an environment capable of building meaningful connections is beyond quantifiable figures [2,9,10]. As the first mandate of this intervention framework, education and human connection provide conditions such that individuals can and believe that they can achieve better health.

Continuity of Care

Likewise with all healthcare services in the community, maintaining continuity of care is a pillar of medicine and the promotion of patient health and well-being [11]. In parallel with the mandates of the Mandela rules, healthcare in the carceral setting should maintain all resemblance to the community, including its services over time [4,11]. While the transition of healthcare from the CSC to the respective province or territory is a significant barrier to continuity, this paper argues that it is an opportunity, as discussed in the previous section on education. In addition to easing stains during file transfers, the ability to recommend “new” services, such as safe needle exchanges that receive little to no attention within the CSC, is a clear advantage [2,11,15,16].

Although this paper will not discuss the specifics of its administration, these principles of continuity of care are discussed below. First, the CSC should provide a complete and comprehensive file of the services and history provided during the course during which the individual was incarcerated. Such information should be delivered to the HLO in a timely manner to ensure the ease of one’s transition over the rapid events post-release. Second, the presented file should ideally be covered by as few individuals as possible to ensure consistency in personnel and information available for a given individual. Together, both steps should enable the HLO to act as a intermediary not only for information but also for emotional stressors released on an individual. Similarly, the continuity of care by the HLO from the CSC to the provincial or territorial health authority should promote humanity and interpersonal relationships to foster trust and belonging. Furthermore, while an individual is crossing a jurisdictional limbo, they should feel a sense of care and compassion from those who have access and authority over their file. As a common complaint in the community healthcare setting is the lack of compassion of healthcare personnel, the role of the HLO should be to act as an individual that is consistently present and is consistently available for questions and concerns. The third point is essentially the result of continuity of care; by working with quality and knowledgeable personnel, the jurisdictions of health are not just bridges; they serve as a jumping point for new services previously unknown. The work of the HLO not only provides ease in one release from federal custody, but helps it achieve better health outcomes, where the system and its people work together. Thus, the second mandate of this intervention framework seeks to further the aforementioned concept of the “duopoly of responsibility”. When both the individual, care providers, and the system in general are aimed at improving health and wellness, the individual is more likely to continue working towards such objectives [5,6,11].

Conclusion

While the superficial mandate of this intervention is education and the promotion of continuity of healthcare, its primary strength is the individual that work within it. Under the guidance of the HLO, evidence-based care is provided within an environment that promotes interpersonal relationships towards the betterment of one’s health and wellness. While its no question that the present system is dysfunctional, the same system still has the power to make progressive change. It is this resilience that will continue to change the path of Canada’s carceral system such that justice and human rights can be achieved within tomorrow’s criminal-justice system.

References

1. Scallan E, Lancaster K, Kouyoumdjian F. The “problem” of health: An analysis of health care provision in Canada’s federal prisons. Health (London). 2021 Jan 1;25(1):3–20.

2. Gardner TM, Mistak D. Caring Less: Treatment of Mental Health and Addiction in Carceral Settings. In: Weil AR, Reichert AJ, Feiden K, editors. Reducing the Health Harms of Incarceration [Internet]. Washington, DC: Aspen Health Strategy Group; 2022. p. 43–59. Available from: https://www.aspeninstitute.org/publications/reducing-the-health-harms-of-incarceration/

3. Government of Canada. Corrections and Conditional Release Act [Internet]. S.C. Jun 18, 1992 p. 192. Available from: https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/c-44.6/page-1.html

4. United Nations. Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners [Internet]. Geneva, CH: First United Nations Congress on the Prevention of Crime & the Treatment of Offenders; 1955 p. 14. Available from: https://www.un.org/en/events/mandeladay/mandela_rules.shtml

5. United Nations. Compendium of United Nations Standards and Norms in Crime prevention and criminal justice [Internet]. Vienna, AT: United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime; 2016 p. 1–454. Report No.: V.16-00685. Available from: https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/justice-and-prison-reform/compendium.html

6. Venters H. The Hidden World of Correctional Health. In: Weil AR, Reichert AJ, Feiden K, editors. Reducing the Health Harms of Incarceration [Internet]. Washington, DC: Aspen Health Strategy Group; 2022. p. 25–39. Available from: https://www.aspeninstitute.org/publications/reducing-the-health-harms-of-incarceration/

7. Kouyoumdjian F, Schuler A, Matheson FI, Hwang SW. Health status of prisoners in Canada. Canadian Family Physician [Internet]. 2016 Mar;63(3):215–22. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4984599/

8. McLeod KE, Butler A, Young JT, Southalan L, Borschmann R, Sturup-Toft S, et al. Global Prison Health Care Governance and Health Equity: A Critical Lack of Evidence. Am J Public Health. 2020 Mar 1;110(3):303–8.

9. McLeod KE, Korchinski M, Young P, Milkovich T, Hemingway C, DeGroot M, et al. Supporting women leaving prison through peer health mentoring: A participatory health research study. cmajo. 2020 Jan;8(1):E1–8.

10. McLeod KE, Timler K, Korchinski M, Young P, Milkovich T, McBride C, et al. Supporting people leaving prisons during COVID-19: Perspectives from peer health mentors. IJPH. 2021 Oct 18;17(3):206–16.

11. Hu C, Jurgutis J, Edwards D, O’Shea T, Regenstreif L, Bodkin C, et al. “When you first walk out the gates…where do [you] go?”: Barriers and opportunities to achieving continuity of health care at the time of release from a provincial jail in Ontario. Knittel A, editor. PLoS ONE. 2020 Apr 10;15(4):e0231211.

12. Coyle A. Chapter 2: Standards in prison health: The prisoner as a patient. In: Enggist S, Møller L, Galea G, Udesen C, editors. Prisons and Health [Internet]. Copenhagen, DK: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2014. p. 6–10. Available from: https://www.who.int/europe/publications/i/item/9789289050593

13. Restellini JP, Restellini R. Chapter 3: Prison-specific ethical and clinical problems. In: Enggist S, Møller L, Galea G, Udesen C, editors. Prisons and Health [Internet]. Copenhagen, DK: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2014. p. 11–8. Available from: https://www.who.int/europe/publications/i/item/9789289050593

14. Henning C. The Physical and Mental Health of Incarcerated Persons: A Canadian Perspective. Journal of Multidisciplinary Research at Trent [Internet]. 2021 Dec 31;3(1). Available from: https://ojs.trentu.ca/ojs/index.php/jmrt/article/view/341

15. Kouyoumdjian FG, Cheng SY, Fung K, Orkin AM, McIsaac KE, Kendall C, et al. The health care utilization of people in prison and after prison release: A population-based cohort study in Ontario, Canada. PLoS One. 2018 Aug 3;13(8):e0201592.

16. Kronfli N, Dussault C, Bartlett S, Fuchs D, Kaita K, Harland K, et al. Disparities in hepatitis C care across Canadian provincial prisons: Implications for hepatitis C micro-elimination. CanLivJ. 2021 Aug 1;4(3):292–310.

Note. The term “purposefully” is used in the context of legality legislation and statute ↩︎

Note. While not discussed in this paper, we acknowledge the transparency and effectiveness of such a system must be diligently supervised by the CSC’s external ombudsperson: the Office of the Correctional Investigator. ↩︎